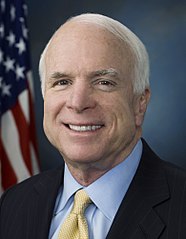

Just three months after the death of John McCain (which I reflected on in my September newsletter), we have lost another fine leader, perhaps the best of my generation, President George H.W. Bush.

Bush was a seasoned executive before he served in the White House; he was a World War II veteran, businessman, congressman, ambassador to the United Nations, representative to China, director of the CIA and Vice President under Ronald Reagan. This experience at various levels of national service made him a highly qualified public servant.

Bush’s White House was organized, competent, and easy to work with on trade and international issues. Applied Materials and other high-tech companies benefited because his Administration listened.

My overriding Morganism is that you must build and model a culture of trust and respect. Interacting with Bush and his various organization teams over the years always impressed me that he sought people that were competent, engendered respect, and were themselves respectful.

My wife Becky and I were present at Bush’s Inauguration and also the 1988 Inaugural Ball that he and Barbara Bush attended in Union Station. As they ascended the stairs to the dais I saw him take on an aura of transformation—he became our leader, the President of the United States.

In 1988, I joined the National Advisory Committee on Semiconductors (NACS). The NACS Committee was set up during the Reagan Administration but it was most active under George Bush. As Vice President, Bush had come to Applied in a campaign stop two weeks before he was elected President. Our team did an outstanding organizational job—a tent for over 1000 people, at least 30 camera people plus reporters, and a large multijurisdictional security detail, as we hosted the Vice President and Governor Deukmejian and my favorite Republican leader, Senator Becky Morgan.

The next day I ran into one of the Applied employees from the drafting department who appreciated getting to see and hear from these leaders during a workday. She said: “Jim, I am a Democrat but yesterday was one of the best days of my life.”

A culture of respect and trust begins with a commitment to hiring excellent people. Bush had a tough inner decisiveness but he showed respect and trust for his experienced team and they for him. Throughout his administration, he sought help and advice from a talented group of staff and advisors, including Secretary of State James Baker III, national security adviser Brent Scowcroft, and General Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. I’ve learned that nothing beats working for excellent, principled managers, and Bush certainly fit that bill.

One of the highlights of his term as president was working closely with Mikhail Gorbachev to usher in the end of the Cold War, including the reunification of Germany, and the breakup of the Soviet Union, with the largely peaceful regime changes in the Eastern Bloc. As the New York Times noted, Bush chose a collaborative approach to this momentous event and gained Gorbachev’s trust.

If you don’t develop processes collaboratively, ideally requesting but also accepting input by all stakeholders, your culture will be plagued by simmering resentments and sometimes even sabotage. Before attacking Iraq in the First Gulf War, Bush obtained support from the United Nations Security Council and a coalition of 28 countries. The ground war was over in 100 hours.

Thinking back to those times reminds me of the approach we took to collaboration at Applied Materials. These are the guidelines I circulated among my executive team members:

- Agreements must be perceived as fair by both parties. Goals should be attainable and payoffs realized.

- Long-term relationships have greater payoffs financially and in personal satisfaction than quick reward of advantage.

- I don’t expect to make money before my partner makes money.

- I keep my partners apprised of both the success and failures of my efforts.

- I believe my contribution is critical, but that my partners can be successful without me.

- All business relationships require open and honest communication, teamwork, and patience.

Principles such as these clearly informed the approach that President Bush followed when faced with national challenges, and in working day-to-day with the House and the Senate during his term as president.

A culture of respect and trust, and a willingness to collaborate with opponents remain central to President George H.W. Bush’s legacy in Washington.

I hope that the topics in this year’s newsletters have helped to inspire you to think about what you can do to shape the culture within your organization.

To your success,

Jim Morgan

I’d like to hear from you on this topic, please comment below.

Successful collaboration, planning, and implementation are possible when all stakeholders—public, private, and nonprofit—are engaged with goodwill, determined to achieve a collective solution.

Successful collaboration, planning, and implementation are possible when all stakeholders—public, private, and nonprofit—are engaged with goodwill, determined to achieve a collective solution.